NEW HAVEN — Gailya Brown can’t contain her enthusiasm. It bubbles out of her as she breaks into a joyous dance.

It’s hard to believe the life she lived before she found the fellowship in the Imani Breakthrough program at Varick Memorial AME Zion Church, 242 Dixwell Ave.

“I did drugs. I did everything around the corner. … I drank, I raised hell … I was on the street, I was homeless a couple times. I was in every one of those shoes.”

That’s not the Gailya Brown you’ll meet today. Now, the love and joy spring from one source: God.

“When he come bubbling through your stomach and out your heart, you feel it,” she said.

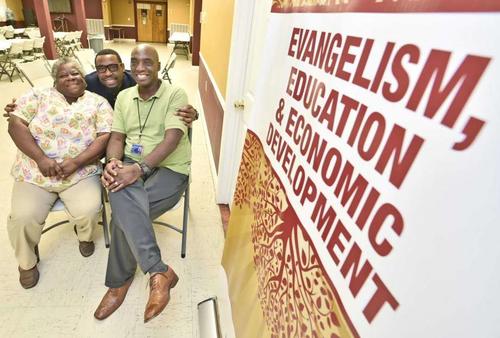

Brown was in the first group of 25 who met at Varick for 12 weeks in a program that uses the power of spirituality to help people conquer their addictions to alcohol and other drugs.

Supported by the state Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and the Psychiatry Department of the Yale School of Medicine, Imani Breakthrough (“Imani” means “faith” in Swahili) was focused on the black community through the churches that are the spiritual rock for many African Americans. It was so popular that the second session, which began recently, was increased to 40 participants.

The program also is held at three other primarily African-American churches in Connecticut — in Bridgeport, Hartford and Waterbury.

“The reason they chose us to do this program is people feel more protected or they let their guard down coming to a house of worship and where they feel like they’re not being judged,” said Sylvia Cooper, one of the lead facilitators at Varick.

“The ultimate goal is for people to get in treatment or for those who are in treatment to continue on with their treatment,” she said.

Imani Breakthrough is open to anyone who wants to be free of addiction.

“Some are currently using and they may be those who are prior users who just want to stay clean,” Cooper said.

For some, the weekly meetings in the church basement may be their last hope. “They’ve been estranged from their family … and they want to be engaged with their family members,” Cooper said.

While the group members come from all walks of life, and range in age from 18 to 65, by the second week strong bonds are forming among the participants. “We don’t treat and teach,” Cooper said. “It’s an environment of a safe haven. A lot of folks are homeless. … They’re looking for employment skills and some are highly functioning. They have jobs [and families] and they’re just looking for coping skills.”

Brown is a member of another church but spends much of her time at Varick each week volunteering in the soup kitchen and food pantry.

“I love people and I love taking care of people so this is my home,” she said.

She laughs with fellow group member Michael Willoughby about the incidents and things that were said during the weekly meetings. “It helped me a lot because a lot of stuff that was going on with me … all our stories were similar together.

“I started telling stories about how I was abused when I was young and growing up with the bottle,” Brown said.

She also was involved in a bus accident four years ago and has been treated for anxiety. She said she stopped drinking 12 years ago.

“This was my first therapy with meeting everybody and all of us sharing. … It was relief. We all shared; we cried; we prayed.”

The program is based on “eight dimensions of wellness,” Cooper said: emotional, health, occupational, financial, spiritual, wellness, intellectual and physical, and focus on “the five R’s”: roles, resources, responsibilities, relationships and rights. There is a $10 stipend given each meeting to help with transportation and other needs and participants share a meal. The 12-week program is followed by weekly follow-up check-ins with coaches.

Meetings start out with candlelight and silence. “We basically calm the room by being silent,” Cooper said. “Just calming the room by listening … just trying to home in on peace and silence.”

Then they might talk about how they would deal with a negative person if they had to return something to the grocery store. “People are like, ‘Wow!’ because they can’t get anywhere yelling and acting unseemly,” she said. “People can hear me more if I self-advocate and communicate. I can get what I need.”

“Each week we had a different topic that we talked about and worked on,” Willoughby said. “But the main thing was about us advocating for ourselves, opening our mouths and getting the help we needed.”

The Rev. Kelcy G.L. Steele, senior pastor of Varick, said that when a parish member proposed that Varick get involved, “of course we said yes because we saw the need in our community. … The facilitators are members and leaders of our church who have been trained.”

Steele keeps his involvement low “in order to give people their privacy,” he said. “The purpose of the program is peer empowerment.”

Willoughby said he joined Imani Breakthrough “because I was struggling and I’m the type of individual where I have to be honest. … Once I’m able to be honest with myself, I’m able to reach out and ask for help.

“One of the things this program has done for me is being able to advocate for myself,” Willoughby said. “It has also given me an opportunity to find resources in the community. It’s given me the opportunity to have a community of like-minded individuals.”

He said he uses drugs “because of pain, emotional pain, not being accepted, not being understood, feeling abandoned.”

In his family, it can be a struggle sometimes because “there’s so many dynamics,” Willoughby said. “But when you get in the midst of other individuals … it’s like one day at a time now for me, trying to stay in the moment, trying to love [and] forgive myself. … We are truly amazing individuals.”

Willoughby, 63, who grew up in New Haven, was reluctant to return because of “all my skeletons and demons.” He left 13 years ago. “I packed one bag and I just dropped everything and dropped everybody. I went from town to town” — Waterbury, Meriden, Middletown, New Britain, finally ending up in Hartford.

He used crack cocaine and drank and had thoughts of suicide. As the first-born in his family, “I just couldn’t live up to those expectations any longer,” he said. “I’ve always tried to make others happy … and I was just miserable.”

But he returned to New Haven because his family needed him and he became clean and sober. He also returned to Varick, where he grew up. “Today what another person thinks about me it’s not my business,” Willoughby said.

The program gave him the opportunity to open up to others. “If you don’t have a place to go where you can talk about what’s going on in your life, you’re subject to going out” and taking drugs, he said.

Now Willoughby is taking classes at Gateway Community College in psychology, sociology and human services. He previously attended Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., which Steele also attended.

Brown, 61, said when she started in the program “it was like an elephant on my chest and water running down my eyes and I couldn’t talk.” But once involved with Imani Breakthrough, “It was a relief,” she said. “I was on Cloud 9 or up in heaven. I was feeling great coming here and I wanted to share I wanted some more of it.”

Steele said that “we as church people forget where we come from and we look down on others with condemnation. But listening to Brown and Willoughby “lets me know that we’re doing the right thing. We preach compassion and not condemnation and we want to be the church of the open door.”

Cooper said that while the program is based in the inner city, the problem of drug addiction is not limited to that community. “It also happens in the suburbs because you can afford it even more,” she said.

She said there are some members who come from outside New Haven and, while about 70 percent are black, there are white and Latino members.

Chyrell Bellamy, an associate professor of psychiatry and director of peer services and research in the Department of Psychiatry, said the purpose was to learn “how to connect with people to strengthen their lives. … How do you help these people to regain the eight dimensions of wellness, which is critical to sustain their recovery?” she said.

Bellamy said the program has financial support for two more years and additional funds to develop a Latino version.

“The one thing I do as a facilitator that I like about the group, it’s almost like making a homemade soup,” Cooper said. “The more everyone adds something to it, the more everyone can eat from it. It becomes very rich.”

For more information about the New Haven program, contact Cooper at 475-224-1448 or coopersylvia0130@gmail.com.

The Bridgeport program is held at Mount Aery Baptist Church, 73 Frank St. Contact Michael Walton at 475-224-1228 or michaelwalton17@yahoo.com or the Rev. Velva Tucker at 203-434-9761 or vjtucker@sbcglobal.net.

by Ed Stannard